| |

| N. Roerich. Christ and Buddha’s roads juncture. 1925 |

Most of the time, the travelers spent in journeys around the princedom. Full of beauty, the valley of Kashmir lay on ancient Asian ways. “Where did the hordes of great moguls pass? Where did the Lost Tribe of Israel escape? Where is the “Throne of Solomon”? Where are the paths of Christ-Wanderer? Where is the glow of the shaman Bon-Po – religion of demons? <…> Everything passed through Kashmir. <…> – the artist wrote down. – And each caravan flashes by like a link in combinations of the great body of the East”9.

Various peoples and tribes left their traces in stone, in costume, in the spiritual culture. This made Kashmir especially interesting for studies.

And again Nicholas Roerich put his landmarks. “On the hayloft, there are sledges – Moscow rozvalni. In the yard, a well-sweep is creaking above the well. <…> And where is that? In Shuya or Kolomna? It is in Shrinagar, “the city of sun”10.

“In the middle of the village, there is a graveyard – a mound strewed with stones – our Northern “zhalnik”. <…> Near the villages, there are remainders of temples and “sites of ancient settlements” – sandy hillocks covering antiquities. Before the evening, rowers sing lingering “hobblers’” songs, and packs of dogs are barking vociferously. From the far North to the South – the same structure of life. Amazing!”11

| |

| Expedition tent. 1927 |

In the mountain village of Gulmarg, where preparations were finishing and the caravan was being formed, numerous problems started arising before the expedition. The issue of the permit for departure was delayed, the English resident and the Maharaja’s authorized person answered all the questions evasively. At last, with great difficulties, the permit was received, and, at the beginning of August 1925, the expedition started out for Ladakh. But they interfered with its advancement. In Tangmart, not far from Goolmarg, a gang attacked the caravan. Seven people were wounded. Nicholas and George Roerichs spent the whole night awake, holding their revolvers ready. Among the attacking people, the English resident’s driver was noticed.

This and the following incidents which took place during the travel testify to the fact that there was a third party which constantly interfered in the relations between the expedition and the governments of countries through which it was passing. It was the English Intelligence Service, which tried to destroy the Roerichs’ plans and make expedition deviate from the itinerary, concerned with the fact that a Russian was passing through the Central Asia, the regions of the English interests. The names of its representatives became known from the documents discovered in the National Archive of India only in 1969. The British General Consul in Kashgar Major Guillan and the British resident in Sikkim Colonel Frederic Bailey created obstacles for the caravan throughout its whole way. Nevertheless, the expedition passed the whole itinerary and completed it with honor.

| |

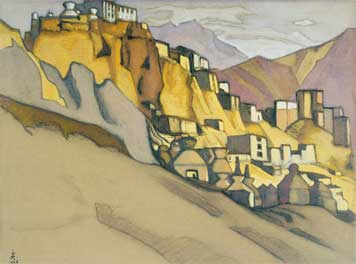

| N. Roerich. Monastery Lamayuru. 1925 |

At the end of August 1925, having passed the Great Himalayan Ridge by an ancient caravan road, the expedition entered a small mountain princedom of Ladakh. “Having passed icy bridges over a roaring river, we seem to be in a different country. The people are more honest, and the brooks are healthy, and the herbs are medicinal, and the stones are multicolored. And in the air itself you feel vigor. <…> Big decisions are possible here”12.

Unlike Muslim Kashmir, Ladakh was Buddhist. Like eagles’ nests, ancient monasteries towered above sheer, inaccessible rocks. “One had to have both a sense of beauty and courageous dedication to get established on such heights”13, the artist wrote.

The “Monastery Lamayuru” on N. Roerich’s painting is lit with the setting sun rays. The steep mountain slopes are cut with numerous caves, square monks’ cells are clinging to the stony rocks. Like a fantastic city, high on sandstone rocks, the monastery is standing.

The Roerichs admired the ancient murals of Lamayuru, studied unknown burial places and old clothes, ancient shrines, and cave drawings.

| |

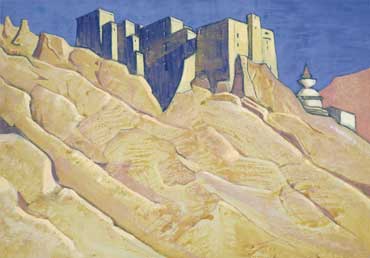

| N. Roerich. Ladakh. Leh. The Royal Palace. Undated |

Leh, the main city of Ladakh, was situated at the intersection of ancient caravan ways. Same as many centuries ago, all wandering, migrating, trading Asia came here. Lamas in red cloths, whimsically dressed monks, keepers of ancient knowledge.

“I am the king of Ladakh, – a lean slender man in a Tibetan turban approached. This is the former king of Ladakh conquered by the Kashmir people. A delicate, intelligent face. Now he is very embarrassed financially”14.

The Roerichs accepted the king’s invitation to stay for a while in his castle. It looks formidable and impressive on Roerich’s painting “Ladakh. Leh. The royal palace”. And next to it, on a sandy rock, a white pyramid of suburghan is sparkling in the sun. “When the sun sets, the whole sandy plane and the sandy rocks surrounding it from all sides, are penetrated with intensive light, G. Roerich told. – The city lying underneath plunges into deep violet haze, and on the plane, like jewels, rows of white stupas sparkle”15.

Stupas (suburghans) are special cult structures erected in Asia in honor of important and memorable events. A huge Buddhist stupa is towering on Nicholas Roerich’s painting “Crossing of the ways of Christ and Buddha”. Behind it, there are broken outlines of the rocks with which the ruins of a fortress and the building of the monastery Sheh are merged. Here, once the ways of two Great Teachers – Buddha and Christ – crossed in space. Tradition has it that Buddha was heading for Altai, and Christ – for Shambala.

| |

| Big stupa in Sheh. Tibet. The photograph is taken

during the Central-Asian expedition. 1925 |

“In Shrinagar, Roerich wrote, an interesting legend of Christ’s stay reached us for the first time. Afterwards, we saw ourselves how wide in India, Ladakh, and Central Asia, the legend of Christ’s being here during his long absence mentioned in the Scriptures is spread”16.

In Ladakh, the artist visited remote monasteries and fortresses, painted ancient mountains, sunsets and dawns… But they had to hurry. Ahead, there was a difficult crossing over the snowy ridges of Karakorum – one of the highest in the world mountain passes. It was necessary to cross it before the autumn North-East wind. On September 19, 1925, the caravan set forward.

Within twelve days, the expedition crossed five passes. On the Sasser Pass, Yuri Roerich was about to die, when rising over a smooth spherical surface of a glacier, his horse almost slipped down. Behind the violet and velvety-brown rocks on the artist’s painting “Sasser Pass”, white smooth giants with pointed snowy peaks are rising.

| |

| N. Roerich. Sasser Pass. Undated |

Ice-coated sheer rocks and snow-storms over the passes, severe frost, which made the hands so cold that it was not possible to either paint or write, horses, slipping off into the icy crevices, cardiac insufficiency and mountain disease – the travelers experienced all the hardships of a mountain itinerary. In the hall show-case, you can see medical equipment from the Roerichs’ expedition first-aid kit.

Hard and difficult was the ancient caravan path, but the severe world of the mountains spreading around was filled with solemn beauty. “To tell about the beauty of this many-day snow kingdom is impossible, Nicholas Roerich wrote down. – Such diversity, such expression of the outlines, so fantastic cities, so multicolored brooks and streams, and so memorable purple and moon rocks”17.

On the paintings of the “Himalayas” series, the mountains are ancient like the Planet itself. The tops lit with the sun at dawn and sunset are flaring with a whole range of amazing colors. Bright, radiant strokes of tempera, to which the artist passed when he was still in Russia, are lying onto the canvases with spell-binding beauty, shine with the gleams of different remote worlds. “It is said that there will be no greater singer of the Sacred Mountains, H. Roerich wrote about her husband’s paintings. – He will remain for ever unsurpassed in this area”18.

Roerich’s mountains are living and breathing. The breath of the Earth and the Universe is mixed in them. The Himalayas are for the painter the symbol of spiritual ascent of man himself, of his thousand-year-old links with this magic space of the planet.

9N. Roerich. Altai – Himalayas. – М.: RIPOL CLASSIC, 2004. – p. 65.

10N. Roerich. Altai – Himalayas. – М.: RIPOL CLASSIC, 2004. – p. 67.

11Same. – p. 70.

12Same. – p. 88.

13N. Roerich. The Heart of Asia. – S-Pb., 1992. – p. 12.

14N. Roerich. Altai – Himalayas. – М.: RIPOL CLASSIC, 2004. – p. 97.

15Quotation after: L. Shaposhnikova. Great Travel. – Book 1. Master. – М.: ICR, 1998. – p. 238 – 239.

16N. Roerich. The Heart of Asia. – S-Pb., 1992. – p. 11.

17Same. – p. 16.

18H. Roerich. On the Threshold of the New World. – М.: ICR, 2000. – p. 309.

|

|

||

|

||