| printer friendly | |||

|

|||

| |

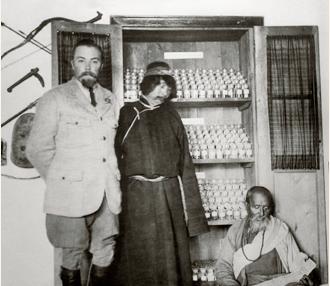

| Kullu. The Urusvati Institute. G.N. Roerich with learned lamas |

The Urusvati Institute, which started actively working in Kullu in 1929, expanded its activities in the 1930s. A special role in its preparation was played by the Central-Asian expedition of 1923-1928. Unique collections formed en route during this expedition gave the opportunity to proceed to research without slowing down the tempo of the work, introducing new scientific methods into the Institute. Considering knowledge from different sciences as something synthetic, not split into different fields, the Roerichs reflected this idea in the Institute’s very structure. Departments of archeology, natural sciences and medicine, a scientific library, and a museum for keeping objects found during the expedition were opened. The departments were subdivided. Under the archeological department were sections of general history, history of Asian peoples’ cultures, history of ancient art, linguistics, and philology. The natural sciences department conducted botanical and zoological studies, meteorological and astronomic observations, and studies of cosmic rays in highland conditions. In the medical department, in addition to studies of ancient Tibetan medicine and pharmacopoeia, a biochemical laboratory was organized where methods of fighting cancer were studied. The whole Roerich family participated in the Institute’s work. Helena Roerich, as its Founder-President, led various of its scientific activities. Nicholas Roerich, who himself represented the synthesis of art and science and considerable organizational abilities, was, just like Helena Roerich, its founder and ideologist. George Roerich, the Roerichs’ elder son, became the Institute Director. Already by that time a well-known scientist possessing a wide cosmic world outlook, he contributed many fruitful ideas to the Institute’s work. The younger son, Svetoslav Roerich, artist and expert in ancient art and local flora, was also a wonderful botanist and ornithologist. The versatility of the knowledge and occupations of each member of the Roerich family, under conditions of their harmonious collaboration and tireless energy, contributed to the success and wide recognition of the Urusvati Institute both in India and far beyond.

| |

| Mixture of medicinal herbs |

Major scientists of various countries collaborated with the Institute and participated in its programs. The closest interaction was established between the Roerichs and scientists and cultural workers of India, such as Chandrasekhar Venkata Raman, Jadadish Chandra Bose, Rabindranat Tagore, Abanindranat Tagore, Ashit Kumar Haldar, Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, Ramananda Chatterjee, Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Teija Singh, Das Gupta, K. P. P. Tampi, R. M. Raval, and others. Among Western scientists, Urusvati’s collaborators and advisors included: A. Einstein, R. Millican, L. Broil, the President of the American Archeological Institute R. Magoffin, the famous traveler and researcher Sven Guedin, the professor of the Pasteur Institute in Paris S. Metalnikov, the orientalist Charles Lanman, the Parisian professor K. Lozina-Lozinsky, the French archeologist K. Bunsson, the director of the Botanical Garden in New York E. D. Merrill, and many others. Until his very arrest, the Soviet academician N. Vavilov maintained correspondence with Svetoslav Roerich on problems of botany. All of them were attracted to the Urusvati Institute not only by the uniqueness of the Himalayas, but by the methods of scientific studies at whose basis lies the methodology of the new system of cognition. The work’s characteristic feature was “constant mobility,” regular expeditions in which the Institute’s “employees and correspondents”[33] took part. “We need,” N. Roerich wrote on this subject, “what Hindus so heartily and significantly call ‘ashram.’ This is the core. But the mental nutrition ‘ashram’ is obtained from various places. Wanderers come quite unexpectedly, each with his own accumulations. But the ‘ashram’ workers do not sit in one place either. At each new opportunity, they go in different directions and replenish their internal reserves. [ . . . ] Actually, any exchange of scientific forces, any expeditions and wanderings become an indispensable condition for any success. At that, people also learn to expand the limits of their specialty. A wanderer can see much. A wanderer, if he is not blind, even unwillingly will see many remarkable things. Thus, a narrow profession, which once seized the whole of mankind, is again replaced by broad cognition.”[34]

| |

| the Urusvati Institute herbariums |

It is necessary, Nicholas Roerich wrote, “both to look up high and to penetrate deep inside.”[35] This implies the expansion of the realm of consciousness, in which the heavenly and the earthly are interwoven to make a single whole, and in which the surface and the depth are constituted by the most important trends in research. At Urusvati, methods of empirical science were combined with metascientific ones. Moral and ethical issues had great significance as well. The founders themselves were highly spiritual and moral people who embodied the new cosmic world perception. Spiritual knowledge accumulated in the Himalayas was experimentally confirmed. It was at Urusvati that they started scientifically to cognize subtle energies, magnetic currents, cosmic rays, and other states of matter. The idea that the cause of many earthly phenomena lies in the Cosmos, in the worlds of a higher state of matter, penetrated the Institute’s scientific concepts. Before the workers opened the boundless character of scientific studies. They took science out of its crisis and rendered groundless the anticipation of the end of science. The new science corresponding to cosmic thinking must have a relationship with the Higher and reach into the infinity of the cognition of the Universe in all its complexity. This relationship was largely characteristic of the Roerichs themselves, and of a few more scientists who clearly understood the significance of interaction with the Higher powers. The energetic world outlook of the new cosmic thinking made a real basis for the Urusvati scientists’ research. In the Institute’s work, much attention was given to the problems of human consciousness, psychic energy, and the influence of the energy of man himself on scientific experiments. All this formed different approaches to laboratory studies.

| |

| N.K. Roerich on the rout of the expedition of 1934-1935 |

In the short period of the Institute’s existence, much was accomplished. The complex Urusvati expeditions traveled across the ancient valley of Kullu, Lahoul, Beshar, Kangra, Ladakh, and Zanskar. The major Manchurian expedition of 1935 also falls within this period. The Institute’s museum was replenished with rich collections: botanical, ornithological, geological, archeological. George Roerich collected very precious samples of Himalayan folklore. Three solid volumes of the Institute’s studies and its workers’ independent scientific studies were published, buildings were erected, laboratory equipment was acquired and put into operation, the library was considerably enriched. Founder-President Helena Roerich, in connection with the Institute’s third anniversary, said: “Don’t let us forget that the valley of Kullu which has collected in itself all the majestic names of humanity starting from Manu, Buddha, Arjuna, all the Pandava heroes, Vyasa, Gesser Khan, is an exceptional area, the scientific value of which only begins to be revealed, but, even at the beginning, it strikes with its very rich material. This takes place in historical, archeological, philological, botanical, geological, and physical aspects. The Institute, as it is already, looks to perform highly fruitful work.”[36] The first success of the Institute’s work allowed the Roerichs to see and elaborate the prospects for its development. “The Station [the Urusvati Institute – L.Sh.] must develop into a city of Knowledge,” H. Roerich noted. “We wish to produce a synthesis of scientific achievements in this city. That is why all branches of science must be represented in it afterward. And since knowledge has the whole Cosmos as its source, the participants at the scientific station must belong to the whole world, that is, to all nations; and, just as the Cosmos is indivisible in its functions, the scientists of the whole world must be indivisible in their achievements, in other words, united in the closest collaboration. The station’s location is chosen absolutely consciously and deliberately, for the Himalayas give countless possibilities in all respects. The scientific world’s attention is directed now at these heights. The study of the new cosmic rays that give to mankind new, most precious energies is only possible on heights, for all that is most subtle and precious lies in the purest layers of the atmosphere.”[37] A grandiose plan – a city of Knowledge – was conceived, which was to become the world catalyst for the new science of cosmic thinking.” And more: “The foundation of a city of synthetic knowledge is a great world cause, so we can’t simply ask for, but must demand, assistance. Not for ourselves are we working, but for humanity. Everyone is ready to contribute his or her best efforts for the common good. Let others also understand this pure aspiration and light up for the promotion of mankind on the way to synthetic knowledge.”[38]

| |

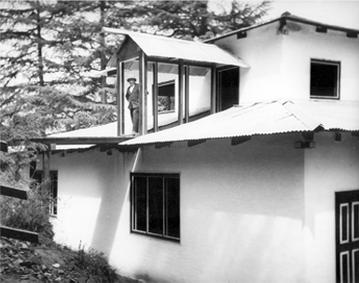

| the Urusvati Institute building the Biochemical Laboratory |

But the plans were not to be realized. Historical events happened such that not only did the city of Knowledge so desired for science not appear, but also even its first result, the Institute of Himalayan Studies, was deprived of any possibility for future development.

At the beginning of the 1930s, a world economic crisis began. Organizations that had financed Urusvati could not continue to do so. “Suddenly American financial crises thundered,” N. Roerich wrote with bitterness. “European confusion rumbled. Funds were cut off. It will not be possible to maintain a whole scientific institution on paintings alone. They gave all that they could, and more can be taken nowhere. Nevertheless, general interest in the Himalayas is constantly growing. Annual expeditions are sent here from all parts of the world. New excavations reveal the most ancient cultures of India. Precious manuscripts and murals are discovered in old monasteries of Tibet. Ayurveda again acquires its former significance, and the most serious specialists are again directing their attention to this ancient heritage. [ . . . ] Everything is there, but there is no money.”[39]

Then World War II started, and the relations that had intellectually nourished the Institute’s activities were ruptured. “First we found ourselves separated from Vienna,” Nicholas Roerich noted, “then from Prague. Warsaw was cut off. [ . . . ] Gradually, contacts with the Baltic countries became difficult. Sweden, Denmark, and Norway disappeared from correspondence. Bruges fell silent. Belgrade, Zagreb, and Italy plunged into silence. Paris finished. America turned out to be at the back of beyond, and letters either did not reach their addressees at all, or wandered around over distant seas and stayed under censorship for a long time. Now you cannot write any more to Portugal. From Riga, a telegram gets no answer. The Far East has fallen silent. [ . . . ] Switzerland has turned out to be a bewitched country. You can’t write anywhere. And it is impossible to write to the Motherland as well, and they asked about herbs. Who knows which letters were lost. Who is alive, and who has already moved to a better world?”[40]

He called this state of separation from the world an island. The Institute, whose activities relied on international relations, naturally could not continue working, even if funds were there. The Institute had to be suspended. Collections were put into boxes, laboratory equipment was dismantled, residential quarters where visiting scientists stayed were closed. The Institute that had so successfully been working seemed to have ceased to exist. In a few years, the war finished. India, after a bloody conflict between Hindus and Muslims, gained independence. In 1947 Nicholas Roerich died; in 1955 Helena Roerich passed away. In 1957 George Roerich went to the Soviet Union and in 1960 died there unexpectedly. Only Svetoslav Roerich remained.

| |

| The Roerichs' villa in Kullu |

L. Shaposhnikova, the current General Director of the N. Roerich Museum and Vice-President of the International Center of the Roerichs, met S. Roerich in 1968 when she visited India with a delegation of the first Jawaharlal Nehru Prize Winners. And in 1972 Svetoslav Roerich invited her to visit the Roerichs’ villa in Kullu. It was then that Ludmila Shaposhnikova for the first time saw the Himalayas, the ancient valley of Kullu, and the Roerichs’ house standing on a wooded slope above the ancient village of Naggar. Svetoslav Roerich showed her the Urusvati Institute, which was located in a deodar grove a little higher on the slope. Along a narrow path, we rose to a cozy platform covered with bright-green grass, L. Shaposhnikova remembers. There, in the middle of the trees, the two buildings of the Institute of Himalayan Studies stood. One of them was still bearing the sign – “Urusvati.”

“All of this slope and grove,” Svetoslav Roerich gestured, “belong to the Institute. These are the twenty acres of land that my father, Nicholas Roerich, gave for this purpose. In this house,” he pointed at a two-story building, “foreign and Indian collaborators lived and worked. And further you see the laboratory building.”

A little to the side, down the slope, there was a pile of stones that obviously used to be the foundation of some structure. It turned out that there was a house where the Tibetan lamas lived who helped George Roerich with his historical and linguistic studies.

We started to examine the house. Our steps resounded in the empty premises, rooms followed one another. In one of the rooms, we stopped before a door. A massive lock hung on it. Its rusted mechanism long would not yield to the key. At last, it opened with a creak, and we found ourselves in a big room. The light could hardly penetrate through the chinks of tightly closed shutters. When our eyes got used to the darkness, I saw boxes standing everywhere. They were many, piled on top of each other, covered by a thick layer of dust. Glass cabinets stood along the room’s walls.

“Our collections,” Svetoslav Roerich said shortly.

Here collections partially left from the Central-Asian expedition and collections formed by the Himalayan expeditions by the Institute’s collaborators were kept. I saw before me unique, rich material untouched by a scientist’s hand for several decades. The cabinets and boxes contained precious ethnographical, archeological, and other kinds of collections. The ornithological collection comprised about 400 species of birds, some of which have already now disappeared. The botanical collection represented the complete flora of the Kullu valley. The geological collection contained many rare minerals. Zoological, pharmacological, and paleonthological collections were also kept here.

| |

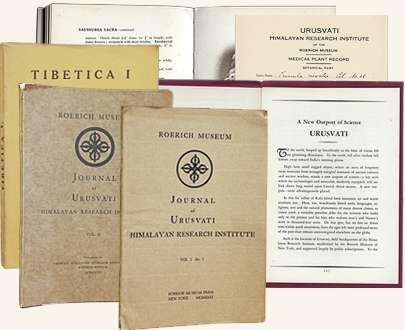

| Works from the Urusvati Institute library |

We passed to the next room, where shelves of books stretched along the walls. The library numbered more than four thousand volumes, which included many rare editions. The books had not been taken from the shelves for a long time, the equipment had never been used… But still, all that Svetoslav Roerich showed me did not produce a depressing impression of neglect and decay. It seemed that people left those premises not so long ago, that for circumstances beyond their control they were unexpectedly and suddenly distracted from interesting work. They only had time to pack the collections and lock the libraries’ and laboratories’ doors…

“This is what Urusvati is now,” Svetoslav Roerich sadly lowered his head. “But the Soviet scientists could work here?!” and his eyes smiled. “Both my father and brother spoke about it more than once. Why don’t Soviet and Indian scientists work here together? All this,” he looked around, “would be at their disposal. Russians started, Russians must continue…”

And this theme “Russians started, Russians must continue” sounded in our talks the whole day.

“You must know,” Svetoslav Roerich said, “that this Institute is not just another scientific institution. The future of science lies in it. Back then, during the war and after, the Institute’s fate was not easy, and the research and scientific methodology that had been emplaced on it were interrupted. They were emplaced not by us, the Roerichs, but by our Teacher who created the Living Ethics and whose plans we were implementing. You know, everything was planned very interestingly and was executed even more interestingly. All those acts in which we participated contained not only the future of the new science, but also the future of the evolution of mankind, its transformation, its new forms of existence.”

More and more often it resounded: New epoch, new cosmic thinking, new science. And in a few days, Svetoslav Roerich asked me to pass his offer on to the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. He wanted a group of Soviet scientists to arrive in Kullu and settle the problem of joint collaboration with India in the Institute of Himalayan Studies. I agreed, and, upon arrival in Moscow, passed all this on to those on whom the fulfillment of Svetoslav Roerich’s request depended. But the scientists did not show much interest in all that; the situation was changing, the difficulties of what was planned were increasing. At that time, in the eighties, despite all efforts nothing could be settled. But this did not mean that Svetoslav Roerich’s suggestion had no future. Many years have passed since then, the USSR has disappeared, separate states have been formed in its place, Svetoslav Roerich has transferred to Russia the heritage of his parents. The N. Roerich Center-Museum appeared in Moscow. In Kullu, the International Roerich Memorial Trust was formed, which included representatives of the central government of the country, the Government of the Himachal Pradesh State. The Trust’s Board of Trustees included Russian scientists and employees of the Russian Embassy. The government of India and the state financed many things in the Roerichs’ estate, in contrast to the attitude of the Russian Government towards the N. Roerich Center-Museum in Moscow. The museum survived and is still working only through the donations of the Russian people.

| |

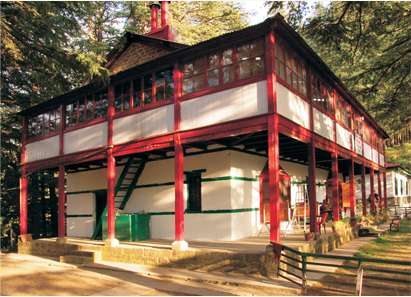

| The Urusvati Institute building |

In 1993 Svetoslav Roerich died, the last of the great Roerich family. After his death, I was a few times in Kullu, visiting India as a member of the International Roerich Memorial Trust Board of Trustees. And every time, I encountered something new – a Museum of the Himalayan Traditional Art in one of the Urusvati buildings, new structures for artistic exhibitions and scientific symposia, an open theatre on the slope of the hill where the Institute was situated. The last visit as part of the delegation of the International Center of the Roerichs, invited by the Karnataka State Government for the celebration of Svetoslav Roerich’s 100th anniversary, was especially interesting for me. Representatives of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences with its Vice-President G. Foursey visited Kullu with us. We were all interested, first of all, in the problem of the renaissance of Urusvati, this unique Institute of new science. The work that had been conducted at the Roerichs’ estate in Kullu did not yet resolve this important issue, though the laboratory building was already being repaired. But India can hardly be blamed for this. Having discussed in Kullu a number of questions related to the Urusvati renaissance, we undertook steps in this direction. The Unified Scientific Center for Problems of Cosmic Mentality (USC CM), established on the basis of the International Center of the Roerichs, was informed about intentions in regard to Urusvati, and its Board of Directors deemed it necessary not only to initiate the process of the Institute’s renaissance, but to take part in it as well.

At the meeting of the International Roerich Memorial Trust Board of Trustees (IRMT) in the spring of 2005, a draft Protocol of joint intentions of the International Center of the Roerichs and the IRMT was presented. The question of the Urusvati Institute renaissance took an important place in it.

The points of the draft were discussed and approved in principle.

It was decided to work on the Urusvati Institute of Himalayan Studies’s renaissance along two trends: research-scientific and as a memorial-museum; this is to be realized by joint efforts of Indian and Russian scientists. It was suggested that concrete programs be elaborated to develop the Protocol of the joint intentions of the ICR and IRMT.

On the whole, it should be noted that important positive decisions regarding the Roerich Museum-Estate in Naggar were made as a result of the attention of the Himachal Pradesh Government and its Head Minister personally and of the support of the Embassy of the Russian Federation in India, including the personal support of Ambassador V. Troubnikiv.

|

|

||

|

||